O. megalodon, my megalodon. The gargantuan shark that prowled the Miocene seas has long captured the imagination because of its stupendous 60-foot length—three times the size of the largest great white sharks. But now, a team of researchers suggests that the extinct apex predator’s body shape was slightly different than expected.

The enormous O. megalodon went extinct around 3.6 million years ago. Newborn megalodons were 6 feet long and may have had an appetite for their siblings; recent studies on the species have generally estimated the adult sharks to grow between 50 feet and 65 feet long (15-20m).

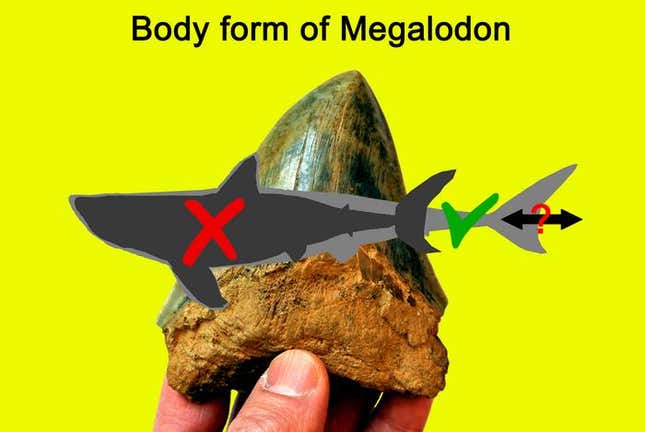

The team’s work—published in Palaeontologia Electronica—suggests that O. megalodon was not as bulky as the great white shark, based on a discrepancy in two previous calculations of one megalodon individual’s length.

Megalodon remains are fragmentary, and inferences about the shark are generally made from its fist-sized teeth and vertebrae. In lieu of a complete (or at the least, more articulated) fossil, paleontologists have based the animal’s dimensions on its living relative, the great white.

“Otodus megalodon was previously envisioned to be a fast-swimming ‘warm-blooded’ shark, just like the modern great white shark, and that was the primary reason why the modern great white shark was used as a model for the body form of O. megalodon,” wrote Kenshu Shimada, a paleobiologist at DePaul University in Chicago and co-author of the study, in an email to Gizmodo.

But several findings have caused that reasoning to shift: after O. megalodon was confirmed to be warm-blooded, a different research team found the modern, slow-moving basking shark was also warm-blooded—indicating that the sluggish swimmers could just as easily have warm blood. Review of O. megalodon’s scales published last year by a team including Shimada then indicated the apex predator was, indeed, a slower swimmerthat would probably swim fast only in short bursts while hunting.

Philip Sternes, a biologist at University of California at Riverside and co-author of the new paper, said in a university release that a better model for O. megalodon's shape may be the mako shark. That checks out: the shortfin mako is the ancient shark’s closest living relative, according to the Australia Museum. An endangered species, the shortfin mako is also the fastest shark: It can hit 46 miles per hour (74 kilometers per hour) in short bursts, according to the Smithsonian Institution.

“Our study suggests that we need to think ‘outside the box’ when it comes to inferring the biology of O. megalodon,” Shimada said. (Which is a relief, because imagine the logistics of megalodon-sized box.) While O. megalodon was still an absolute unit, it was likely more slender; basically the Victor Wembanyama of the ancient ocean. Sternes added that, with its skinny, elongated build, the megalodon may not have fed as frequently as previously thought.

Alas, food availability is a prime suspect for what may have killed off the ancient shark. A team including Shimada posited that great white sharks may have outcompeted their larger relatives, leaving them as the largest lamniform in the sea.

More: Extinct Megalodons Swam Slower to Eat More, New Research Suggests

.png?w=700&c=0)