Darwin Núñez is a striker. Strikers are paid to kick the ball into the goal. And Darwin Núñez is bad at kicking the ball into the goal.

You know this even if you’ve watched him play only a single game. Since joining Liverpool, he’s averaged 4.5 shots per game. Heck, you don’t even need to watch a whole game — just tune in for 20 minutes of any random Liverpool match, and chances are you’ll see Núñez miss a chance.

It’ll probably be a big one, too.

The analytics company Opta defines a “Big Chance” as “a situation where a player should reasonably be expected to score, usually in a one-on-one scenario or from very close range when the ball has a clear path to goal and there is low to moderate pressure on the shooter.” Despite starting only 19 games last season, Núñez ranked third in the league in missed Big Chances (20). This season, he’s all alone in first, with 18 missed.

Liverpool paid €85 million to sign Núñez. Combine that piece of information with all of the above information, and there’s really only one conclusion to be made: Liverpool screwed up.

And yet, Liverpool currently have a five-point lead atop the Premier League table. It’s late January, and their only loss came in a game that produced a massive refereeing scandal and saw two of their players sent off. How could that be possible with all of that money devoted toward one player who keeps missing the goal?

Well, I’m here to let you in on a dirty little secret: It’s not just Núñez. Everyone is bad at kicking the ball into a goal, and by focusing on all of his misses, you’re missing something as well: Darwin Núñez might already be one of the best players on the planet.

Why scoring is so hard

Finishing is all that matters, and it kind of doesn’t matter at all.

The outcome of any individual match is most directly determined by which team was better at converting its chances into goals. Creating a lot of chances is helpful, and creating a lot of good chances is even better, but over the course of a single 90-minute game, none of it matters as much as simply kicking the ball into the goal. Everyone inherently knows this to be true, whether or not they’d like to admit it. We’ve all seen games where a theoretically better team creates way more high-quality chances than its opponent, but the underdog connects with one well-placed shot from outside the box or executes on a pre-planned set piece and ends up winning the game.

Consider the correlation coefficient between the points a team wins in a game and all the different stats we use to gauge how well teams are attacking. When we look at every match played in the Premier League since 2018, the correlation coefficient between the total number of shots a team takes and the number of points it wins in a given match is 0.29. For expected goals created, or xG, it’s 0.45. And for shot-conversion percentage, it’s 0.51.

So what do these numbers mean? A coefficient of 1 would indicate a perfectly linear relationship between the two factors: an increase in one would result in an equally proportionate increase in the other. Zero would mean the relationship is totally random. These numbers seem to show that shots and xG don’t matter as much as simply being able to convert chances into goals.

Put more simply, teams that won games since 2018 in the Premier League have converted 17% of their shots into goals, teams that draw score 8.3% of the time, and teams that lose score with 5.2% of their attempts. So when you see a player like, say, Darwin Núñez miss a big chance, he is costing his team in a very direct way. By not converting a 55% chance into a 100% goal, he’s making it less likely that his team will win that specific game.

The problem is that conversion rates from game to game and shot to shot are incredibly random — that’s why the correlations don’t hold steady for the whole season. When we look at each individual season for each team in the Premier League since 2018, the correlation between full-season shot conversion and end-of-season points rises up to 0.6, but the correlation gets well surpassed by both full-season shots (0.83) and full-season expected goals (0.89).

A hot day of finishing will get you three points, but the ability to get lots of high-quality chances is the much more sustainable characteristic. That creates a kind of weird dichotomy for anyone watching or even playing in a soccer game.

If you convert your chances at a higher clip than your opponents in a given match, you’re doing the most important thing better than they are. You’ll feel like you deserved it, and who’s to say you didn’t? But at the same time, you’re just not going to be able to keep it up. (The inverse is true, too: a wasteful performance of lots of great chances in a loss is still a loss, but it’s also the kind of game that will ultimately lead to more success in the future.)

Since 2018, no Premier League team has converted more than 15.7% of its chances over a full season. The team that reached 15.7% conversion? That was Manchester City last year, but even for arguably the greatest English club side we’ve ever seen, that means that they were missing 84.3% of their shots.

Tottenham’s Son Heung-min is probably the best finisher of the modern era of the Premier League, and he’s scored on only around 18% of his shots for Spurs. The uber-poacher of that same era, Leicester City’s Jamie Vardy, scored with just 20% of his shots.

Soccer is a constant failure, with brief flickers of success. Since these shot-to-goal conversion rates are so low, the differences between the best and worst finishers will make only a marginal difference over a full season. The best attackers, then, are not really the ones who shift the odds in their favor since the odds can only go so high. No, they’re the ones who find a way, in the face of constant disappointment, to keep trying … over and over and over again.

Stop looking at all of Núñez’s misses

Núñez fails more than anyone, but that’s largely because he tries more than anyone.

Last season, he led the Premier League with 4.5 shots per 90 minutes. That was the highest rate in the league, by a good margin. Among players with at least 1,200 minutes played, the next most aggressive shooters were Manchester City’s Erling Haaland and Fulham’s Aleksandar Mitrovic, at 3.8 per 90. This season, Darwin is once again at 4.5 shots per 90, once again leading the league, with Haaland, once again, in second at 3.8.

Notice how consistent Núñez and Haaland’s numbers are? That revels another truth about shots: while your team and teammates certainly help, the ability to generate attempts on goal is largely an individual skill.

Still don’t believe me? Here’s the list showing all of the other players to take at least four shots per 90 minutes in a Premier League season since 2016-17:

-

1. Harry Kane, Tottenham, 2017-18: 5.3 shots

-

2. Sergio Aguero, Manchester City, 2016-17: 5.2 shots

-

3. Sergio Aguero, Manchester City, 2019-20: 4.5 shots

-

4. Gabriel Jesus, Manchester City, 2019-20: 4.4 shots

-

5. Mohamed Salah, Liverpool, 2017-18: 4.4 shots

-

6. Philippe Coutinho, Liverpool, 2016-17: 4.3 shots

-

7. Zlatan Ibrahimovic, Manchester United, 2016-17: 4.3 shots

-

8. Sergio Aguero, Manchester City, 2018-19: 4.2 shots

-

9. Sergio Aguero, Manchester City, 2017-18: 4.1 shots

-

10. Mohamed Salah, Liverpool, 2019-20: 4.0 shots

One way to interpret this list is that there are three players to hit at least four shots per 90 minutes in a season twice since 2016. One is Darwin Núñez, and the other two are Sergio Aguero and Mohamed Salah — two of the five or 10 best players in the history of the Premier League. The players who generate as many shots as Núñez has through his first one-and-a-half Premier League seasons are almost all stone-cold superstars. Most of the guys who did it once are or were superstars, too.

And yes, it’s not just about shooting the ball a lot. Not all shots are created equal. Bad shots can actually make your team worse because they eliminate the possibility of a higher-quality attempt being created later in the possession in exchange for a low-quality shot with little chance of going in.

Núñez, though, isn’t really doing that. The average xG value of his attempts since joining Liverpool is 0.15. That’s well below Haaland’s rate of 0.21, but he is taking more shots than Haaland. Plus, the average shot in the Premier League has an xG value of 0.11, so he’s still above that. Add it all up, and among players with at least 30 starts since last season, only Haaland is averaging a higher non-penalty xG rate per 90 minutes: 0.8 to Núñez’s 0.7.

The problem, in so much as there could be a problem here, is that he’s not scoring at a rate commensurate with the quality and quantity of the chances he’s getting.

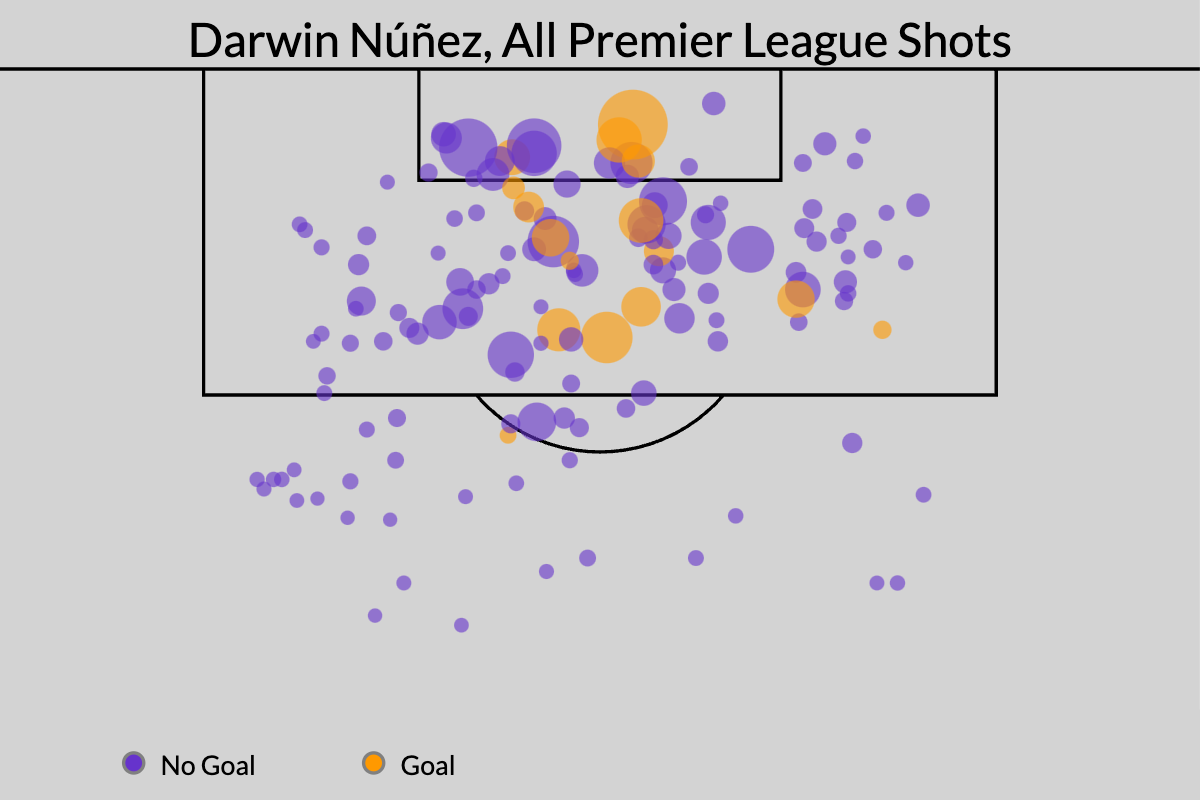

Here’s every shot he has attempted in the Premier League — the larger the circle, the higher the xG value of the attempt:

Núñez has generated 21.5 non-penalty expected goals since the start of last season, and he has scored 16 non-penalty goals. That’s the third-worst level of underperformance of any player in the league over that time frame, and it means there were five-plus goals that Liverpool didn’t score because they couldn’t even get average finishing out of Núñez. Five more goals might’ve meant they were in the Champions League this season, and their domestic success suggests they’d have a real shot at winning their seventh European Cup. Five more goals might mean an even bigger lead in the title race over Man City, too.

That all sounds quite bad — and it looks bad when you watch him play. I get it. But the ability to get all of those shots isn’t an easily replaceable one. Almost no other player is getting on the end of that many opportunities. And Núñez’s ability to get all those chances means he’s able to miss all those chances and still score 0.5 non-penalty goals per 90 minutes. Since the start of last season, that’s tied for third among Premier League players with at least 30 starts. The only players who have been more productive: Haaland and Harry Kane.

That now sounds quite good, and we’re still ignoring two other things: the assists, and the possibility that he finally starts to kick the ball into goal.

Why Núñez is one of the world’s best players

It’s comical at times.

I’ve never seen someone smash a ball so hard into the post or the crossbar from so close to the goal line. I’ve never seen someone dribble through a defense, round a goalkeeper, crash a ball off the post, and then miss the fact that one of his teammates easily slotted in the rebound because he was kneeling inside the penalty area, back to goal, hands over his eyes, wondering what he’d done to upset a clearly vengeful god.

Even when he does something incredible, it’s preceded by something silly.

Just take his goal against Bournemouth in the Carabao Cup. He cuts in and curls one into the top corner, but that’s only after he takes such a terrible first touch that the home fans all start laughing at him.

It just doesn’t really matter how it looks, though. I talked to Liverpool’s former head of research, Ian Graham, about this back in November. He wasn’t talking about Núñez, who was signed while Graham still worked for the club, but the idea still applies:

A scout or a coach would say, “Why do we like this forward?” His team would respond, “He takes loads of really good shots.” The scout or coach would counter, “Yeah, but does he drive inside enough? Does he bring his teammates into play enough?”

“But we’re playing them up front,” Graham said. “He takes loads of good quality shots. There is literally nothing else to say. All other arguments, they’re second-order effects compared to this. But people love to mystify and bring more and more factors into play. A use of the data is just to say: This is the important thing and we might be wrong about it — we sometimes are wrong — but you have to come up with some really good arguments against this one really important thing.”

Bournemouth fans over the weekend took to gleefully taunting him, chanting in unison that Núñez was “just a s— Andy Carroll,” which was certainly not a compliment — but then Núñez scored two goals and silenced them.

Núñez’s timing, understanding of space and sheer physical ability allow him to get into the most dangerous area of the field almost at will. Among all players with 30 starts since the beginning of last season, Núñez leads the way with 8.2 touches inside the penalty area per 90 minutes. And since he’s in the box so often, he’s presented with a specific decision more often than anyone else in the Premier League: to pass or to shoot?

We know he shoots a lot, but the only players averaging more expected assists per 90 minutes than Núñez since the start of last season are Kevin De Bruyne, Bruno Fernandes and James Maddison. While Núñez essentially has nothing in common with any of those players — brute force vs. vision, composure and technical skill — he’s simply on the ball in the box so often that he’s also become one of the most productive creative players in England, too.

Add it all together, and Núñez is tied with Haaland in leading the Premier League in non-penalty xG+xA per 90 minutes at 1.0. And even with the poor finishing, he’s averaging 0.8 non-penalty goals+assists per 90 since the start of last season. Among these 30-game starters, only Haaland, Salah and De Bruyne have been more productive.

Núñez is already keeping elite company, and there are a number of reasons to think he’s only going to get more productive. At 24 years old, he’s just entering his prime. His non-penalty xG+xA rate has risen from 0.93 last year to 1.03 this season. Same goes for his actual production: 0.67 non-penalty goals+assists per 90, up to 0.97 this year. Plus, there’s no guarantee he continues to finish his chances at a below-average rate, either. In his last season with Benfica, he was nearly seven goals above his expected total. Most players, over their careers, tend to regress — positively or negatively — toward their expected goals.

That’s the promise of Darwin Núñez, but the reality is that he doesn’t even need to improve. Just take a look at the list of all the players in Europe’s “Big Five” leagues with at least 10 goals and 10 assists across all competitions this season.

… Just kidding. There is no list. After scoring those two goals against Bournemouth on Sunday, there’s just one player. It’s Darwin Núñez.