In August, the Mongolian government released its National Action Programme for 2024 to 2028. This comprehensive development strategy aims to solve developmental problems and remove roadblocks to successfully implement ongoing projects. It has four goals and a total of 593 planned activities. However, one key project was missing from the list: The construction of the Soyuz Vostok pipelinea 962-km-long extension of the Power of Siberia 2 pipelinewhich connects the gas fields in Yamal in Western Siberia to China via Mongolia. This 2,594-km-long pipeline would add capacity to export 50 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas, in addition to the existing 38 bcm of natural gas currently being exported via the Power of Siberia-1which runs from Yakutia and enters China from Blagoveshchensk on the Russia-China border (see Fig 1.1). The exclusion of the pipeline from this strategy stokes concern about the project stalling, especially since Moscow and Beijing have been unable to agree on key terms for commencing the construction of Russia’s flagship pipeline since last year.

Fig 1.1: Proposed route of Power of Siberia-2

Source: Financial Times

Why is this pipeline important?

From Soviet times, Moscow has been an important energy source for Eastern and Central Europe, with the oil-carrying Druzhba pipeline and the gas-carrying Urengoy-Pomary–Uzhhorod pipeline. After the dissolution of the USSR, relations with Western Europe improved considerably, and the European Union (EU) emerged as a major market for Russian natural resources. This feature would remain unchanged until the Ukraine War in 2022. However, since the late 2010s, new markets have emerged in the East, buttressed by the rise of an energy-hungry China. Moscow was preparing to create new pipelines to the East to diversify its markets away from Europe. This desire could be reflected in its plans to build the Yakutia-Khabarovsk-Vladivostok pipeline, which was renamed the Power of Siberia (PoS) in 2012. The PoS pipeline, operated by Russian Gas giant Gazprom, would carry natural gas from the Kovykta and Chayanda gas fields in Yakutia to Heihe in China, where the Heihe-Shanghai pipeline operated by the China National Petroleum Corporation would commence.

As Russia-EU relations worsened following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, Europe began to be wary of its dependence on Russian energy.

In 2014, a US$ 400-billion deal was signed to supply gas for 30 yearsand construction began in 2015. Four years later, deliveries to China through this pipeline began. As Russia-EU relations worsened following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, Europe began to be wary of its dependence on Russian energy. Despite this concern, a deal was signed between Germany and Russia to build Nord Stream 2, an undersea pipeline between Russia and Germany, which, along with Nord Stream 1, aimed to increase gas supplies to 110 bcm. However, despite completion in 2021, its certification was suspended by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz on 22 February 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine. Europe is planning to phase out the purchase of Russian energy by 2027, and the five-year gas transit agreement with Ukraine is expiring this year, which guarantees gas deliveries to Europe via Ukraine. With markets shrinking for the export of Russian energy, Moscow needs China to purchase its natural gas. In November 2014, a framework agreement was signed to increase deliveries. Several routes were developed and plans were made to build a pipeline across the Altai region, including a possible pipeline plant in Kazakhstan. However, in the end, Mongolia was considered because its geographical location was optimal for the pipeline construction.

Power of Siberia 2

In 2019, during Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev’s visit to Mongolia, the launch of the PoS-2 pipeline, formerly known as the Altai pipeline, was announced. A memorandum of understanding (MoU) was signed between the Mongolian government and Gazprom to jointly assess the feasibility of the pipeline. The following year, Gazprom commenced the design and survey work of PoS-2. In January 2022, the feasibility study was completed, and the preliminary route of the pipeline with an entry point into Mongolia was announced; the local bodies or aimags (regions) in Mongolia were to coordinate the construction of the gas pipeline. Further, in July 2022, L. Oyun-Erdene, Prime Minister of Mongolia, said that the Soyuz Vostok pipeline could begin construction in 2024. Despite the hype and encouragement from the Mongolian government in the pipeline’s development, its exclusion from the national action plan is a matter of concern for Russia.

A memorandum of understanding (MoU) was signed between the Mongolian government and Gazprom to jointly assess the feasibility of the pipeline.

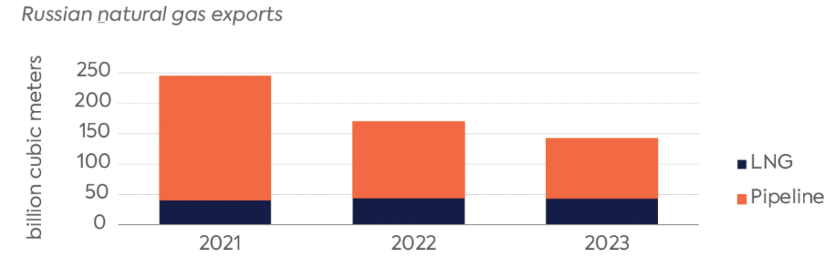

After February 2022, China has emerged as a major buyer of Russian energy; in gas, the domestic consumption in China is around 400 bcm per year, and the number is expected to increase. A majority of gas is imported from Turkmenistan. With gas exports from the PoS-1 pipeline expected to reach the design capacity of 38bcm by 2025, the second PoS pipeline would add an additional capacity of 50 bcm, and the third Power of Siberia-3 pipeline from Sakhalin into China would carry an additional 10 bcm of gas. However, these projects do not add up to the 155 bcm of gas sold to Europe in 2021. Thus, delays in the project will result in Russia losing significant revenue. Since the Ukraine war, several European countries have reduced piped natural gas imports from Russia but continued to import Russian LNG (see Figure 1.2). However, with the imposition of the 14th round of European Union sanctions against Russian LNG, countries have now also reduced their LNG purchase from Russia. In 2023, Gazprom posted a loss of US$ 7 billion. With the Ukrainian gas transit deal unlikely to be extended, Russia desperately needs new markets for its gas. This is why PoS-2 is a pivotal project for Russia.

Figure 1.2: Russia’s natural gas exports

Source: Centre on Global Energy Policy, Energy Institute, S&P global ENTSOG, Interfax

Why does the project appear to be stalling?

While both Gazprom and CNPC have agreed in principle, negotiations on the gas price, volumes, sharing of construction costs, and other related issues are still underway. China wants Gazprom to sell gas we go with the domestic price of gas, which is around US$ 60 per 1000 cubic meters, but on the other hand, the price of gas sold by Russia through the PoS-1 pipeline is US$ 257 per 1,000 cubic meters (see Table 1). Furthermore, Beijing has other concerns, such as Gazprom wanting to control the Mongolian section of the pipeline, which it fears will increase Russia’s influence in Mongolia.

Other issues persist such as making payments while bypassing sanctions against Russia. Even though gas from Russia is the cheapest, China continues to import gas from the Central Asian countries through the Central Asia-China pipelinewith Turkmenistan exporting the highest volume of gas to China. With the construction of the fourth line of the Central Asia-China pipeline, known as line Dan additional 30 bcm of natural gas to China would be exported, bringing Turkmen gas imports to China to 85 bcm. Since Beijing has multiple sources to buy natural gas, it has become a buyer’s market, which is why the negotiations are largely asymmetrical. President Putin’s visit to Beijing in May this year and Chinese Prime Minister Li Qiang’s visit to Moscow in August have not yielded any agreements on PoS-2. Additionally, Mongolia’s exclusion of the Soyuz Vostok pipeline from its national action programme serves as a major impediment to the project.

Table 1: Average Pricing of Russian Natural Gas Export

| Country/Entity | Russian export price per thousand cubic meters in 2024 (average) (in US dollars) |

| Domestic pricing | $60 |

| European Union | $320.3 |

| China | $257 |

| Türkiye | $320.3 |

| Belarus | $127.52 |

| Uzbekistan | $160 |

| Kazakhstan | $180 |

| Kyrgyzstan | $150 |

Note: the pricing may vary

Source: Authors own research

Putin’s visit to Mongolia in the first week of September may be crucial to resolving these issues and bringing the pipeline back on the agenda. Gazprom has lost considerable revenue since the invasion of Ukraine, and any further delays in the pipeline construction will significantly reduce the export capacity of Russian gas. The PoS-2 saga reflects Moscow’s high export dependence on China and how Moscow’s ambitions of pivoting to the East and finding new markets for its abundant energy resources run the risk of being curtailed due to shrinking markets for Moscow. For New Delhi, even though India-Russia ties remain untouched by other geopolitical realignmentsthe growing Russia-China cooperation comes with fears of Indian interests being secondary in Moscow’s calculus, which is a cause of worry in the long term.

Siddharth Jayaprakash is a Research Assistant with the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

.jpg?w=700&c=0)