Camels, caravans and Chevrolets. A 1,200km drive on the fabled Silk Road in Uzbekistan takes us back in time.

Our convoy of black Chevrolet Equinoxes cuts quite a sight cruising down the quiet highway from Samarkand to Bukhara that slices through the barren Kyzylkum Desert. Speed limits are strictly enforced in Uzbekistan, so I set the adaptive cruise control to 90kph to keep a steady pace and engage the Lane Keep Assist function, letting it handle the steering with a gentle touch. It feels like having a co-pilot, freeing me to marvel at the stark, endless landscape. My thoughts drift back to my last road trip in Uzbekistan in 1994 on this very road, in the hardy but crude Mahindra Armada. It was noisy, underpowered and had no power steering or creature comforts to speak of, making driving very tiring. It’s hard to believe that the Armada was the plushest SUV back then, and now, sitting smugly in the happy embrace of the Equinox’s eight-way adjustable powered seat, I marvel at the progress cars have made 30 years on.

.jpg&c=0&w=700) Bactrian camel, once the SUV of the Silk Road.

Bactrian camel, once the SUV of the Silk Road.

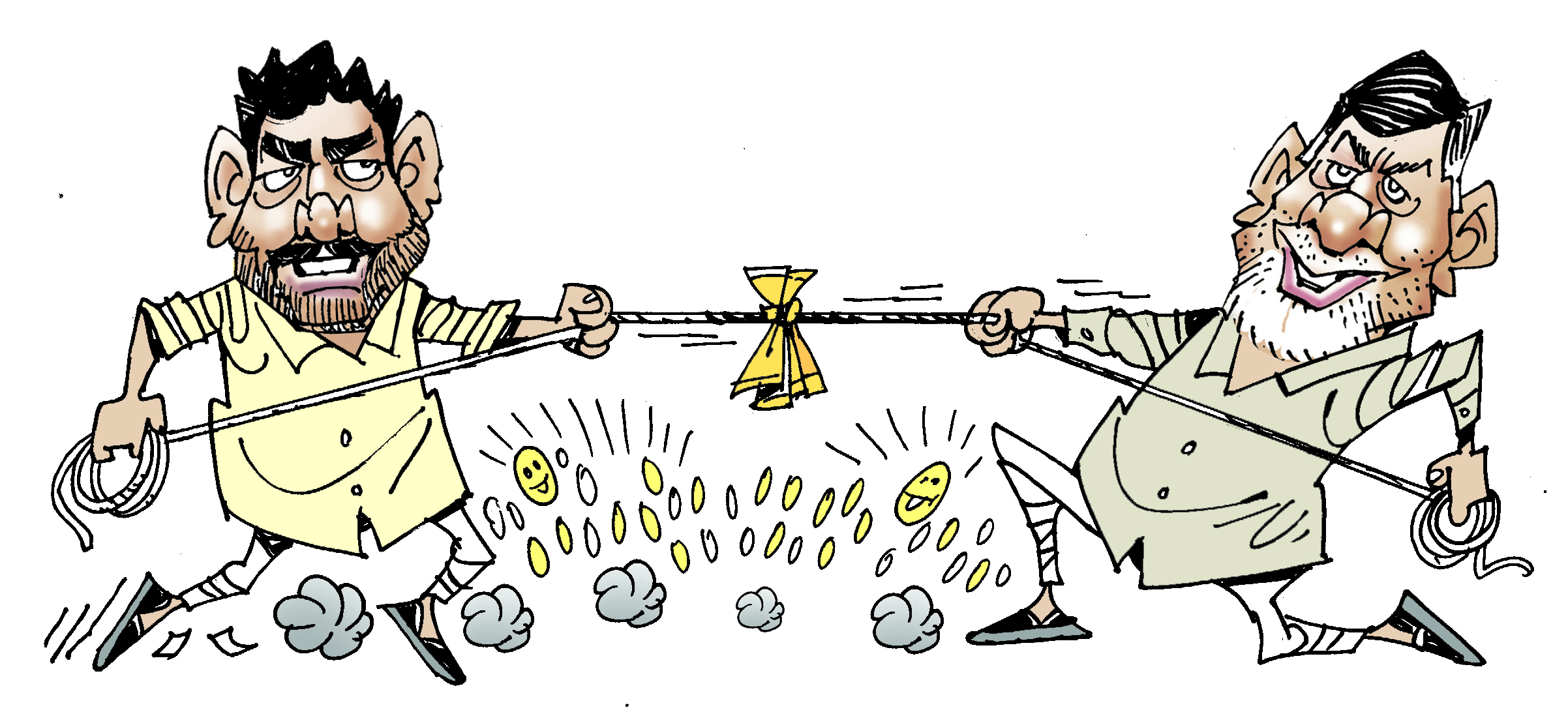

And then I try to imagine the scene 2,000 years ago when this very stretch was the beating heart of the fabled Silk Road, a bustling network of trade routes connecting East and West. What we now effortlessly cover in just a few hours would have been a grueling journey of days, even weeks, atop a trusty camel. The famous double-humped Bactrian camel was the ancient equivalent of an SUV carrying goods and people across tough terrain. The Bactrian camel is still a common sight and an attraction at tourist spots for visitors to take rides on and experience what transport must have been like two millennia back.

We kick off our tour in Tashkent, where streets are wide, clean and lined with trees. They even have an LBS Marg! Well, not quite, but there’s a road named after Lal Bahadur Shastri, our former prime minister who died here in 1966 while still in office. There’s a memorial, too, for him. Tashkent is a fascinating blend of old and new. Historic madrassas and mosques with their shimmering turquoise-tiled domes sit alongside the Tashkent TV Tower, worth a visit just for the 360-degree view of the city.

.jpg&c=0&w=700) Clockwise (L to R): Uzbekistan is famous for its hand-woven carpets; Pilaf or Plov is a popular dish; the humble Somsa is an integral part of Uzbek cuisine.

Clockwise (L to R): Uzbekistan is famous for its hand-woven carpets; Pilaf or Plov is a popular dish; the humble Somsa is an integral part of Uzbek cuisine.

Lunch at Besh Qozon is one of Tashkent’s culinary highlights. Aptly named the Central Asian Pilaf Centre, it’s here that Pilaf or Plov, which is Uzbek (and Russian) for what we call Pulao, is made on an industrial scale. Ingredients are measured in hundreds of kilos, and on average, 3,000 people come here for lunch to wolf down plates of the most delicious Pilaf. Uzbekistan is a gastronome’s delight – from the humble Somsa (Uzbek for Samosa), a ubiquitous snack you can eat off the streets or in the finest restaurants, to varieties of bread and fantastic arrays of salads. Shashlik, Manti (dumplings), Lagman (noodle soup), and lots of veggies are all a part of the varied cuisine.

The Highway Diaries

It’s an early morning start to Samarkand, which is only 300km away but takes a good five hours. Averaging more than 50-60kph on Uzbekistan highways is hard, largely because of the 90kph speed limit, which can suddenly drop to as low as 60kph near towns and intersections. It’s all too easy to get nabbed for speeding as Uzbekistan looks at speeding ends as a source of revenue and not just safety. The good thing is our guide in the lead car constantly warns us of speed-limit changes and obviously does a good job of it because none of us get ticketed after 1,400km of driving or 9,800km if you take the cumulative distance of our seven- car convoy.

.jpg&c=0&w=700) Samarkand is the jewel of Uzbekistan.

Samarkand is the jewel of Uzbekistan.

Roads in Uzbekistan aren’t great, and some highway stretches are infested with potholes, which you have to dodge. The problem is that other drivers are doing it, too, and it is quite the done thing to slalom on the highway to avoid bad patches. Just like back home!

Interestingly, 65 percent of cars run on methane, which is significantly cheaper than petrol, as Uzbekistan has an abundant gas supply. In fact, finding 95-octane fuel for our Chevrolet Equinoxes isn’t easy. Few pumps keep high-octane fuel, which is pretty expensive, too, at 14,500 sum or Rs 95 per liter.

Samarkand is the jewel of Uzbekistan, and if you can visit only one place in this historic town, it’s the Registan Square, surrounded by three madrassas, each an architectural masterpiece.

.jpg&c=0&w=700) 95-octane fuel was neither easy to find nor cheap at 14,500 sum (Rs 95 per litre); About 65 percent of cars in Uzbekistan run on Methane gas.

95-octane fuel was neither easy to find nor cheap at 14,500 sum (Rs 95 per litre); About 65 percent of cars in Uzbekistan run on Methane gas.

The Ulug Beg observatory is a marvel of ancient astronomy and a fascinating historical site. The massive sextant with a 40-metre radius allowed Beg and his team to calculate time to within 25 seconds accuracy per year! Not bad for a time-keeping device built in the 1400s!

By the way, Beg was the grandson of Tamerlane, the founder of the Timurid Empire and Uzbekistan’s greatest hero. And Babar, who founded the Mughal Empire in India, was also a descendant of Tamerlane.

The four-hour drive from Samarkand to Bukhara takes you to Uzbekistan’s more remote regions. The scenery shifts from Samarkand’s historical sites to the more traditional and less developed landscapes. While scenic in some parts, the flat landscape is featureless for most of the way, and you can imagine why this route, which is easy to traverse, was so popular with ancient caravans.

.jpg&c=0&w=700)

Bukhara’s 150-foot-high Kalyan Minaret was the world’s tallest monument when it was built in the 12th century.

Caravans have been replaced by Chevrolets, the dominant brand in Uzbekistan. Eight out of ten cars you see are Chevys, most of which are white. The legacy of the Soviet era lives on in old Ladas, which actually add a bit of color to the roads (they aren’t all white!)

Bukhara isn’t as grand as Samarkand but has a more intimate and ancient charm with its maze of narrow streets and centuries-old markets. These winding alleys were designed for the steady clip-clop of donkey carts, not the bulk of modern SUVs, making it a place best explored on foot. Fortunately, there’s a large public car park where our Chevy SUVs can safely rest while we walk and delve into the city’s rich history.

Bukhara’s 150-foot-high Kalyan Minaret was the world’s tallest monument when it was built in the 12th century and is literally its standout tourist attraction. You can’t miss the Ark Fortress either. This imposing citadel, perched on a hill, is at the heart of Bukhara’s history. It has stood as a symbol of this ancient town’s power for over 1,500 years and is the home of the kingdom’s emirs. The monuments are superbly restored. Walking through these bustling alleyways, you feel like you’ve traveled back in time.

.jpg&c=0&w=700) Convoy of Chevrolet Equinoxes on the road to Khiva, which cuts through the Kyzylkum Desert.

Convoy of Chevrolet Equinoxes on the road to Khiva, which cuts through the Kyzylkum Desert.

That’s especially true of Khiva, our last stop, which feels like an open-air museum, but it’s a day-long drive to get there. The drive to Khiva takes you through the vast Kyzylkum Desert, where the road stretches out in a seemingly endless, arrow-straight line, offering little more than sand and sky for company. Falling asleep at the wheel on such a monotonous stretch is a real risk, which is probably why the police stops us every 30 km or so. But instead of the usual ticket, the officers would politely wave us down, direct us to pull over, and insist we get out of the car, stretch our legs and take a “mandatory” five-minute break. This enforced rest every 20-30 minutes leaves us more annoyed than refreshed but also amused by Uzbekistan’s unique take on road safety.

.jpg&c=0&w=700) As the featureless road is known to make drivers sleepy, police pull drivers over every 30km for a forced break!

As the featureless road is known to make drivers sleepy, police pull drivers over every 30km for a forced break!

Though Khiva isn’t as famous as Samarkand or Bukhara, it’s less touristy and has a unique charm. The walled old city is a UNESCO World Heritage Site packed with stunning madrassas, minarets and palaces that teleport you back in centuries.

Khiva is not a place that’s easy to drive to, but the delightfully intimate experience of Uzbekistan’s past it offers makes it worth a road trip. There are faster ways to get there – either by air or train.

Uzbekistan boasts a fast and efficient rail network, which can be more convenient than driving, but it’s not the most authentic way to explore the country. With the freedom to pause at will, engage with locals and indulge in roadside delights, the Silk Road’s true essence is best experienced – well – by road.

Chevrolet Stronghold

Chevrolet’s dominance in Uzbekistan, with an over 85 percent market share, goes back to the mid-1990s when, after the fall of the Soviet Union, Daewoo was the first automaker to jump into the newly formed country and stitch a joint venture with the Uzbek government to make cars. Uzbekistan has historically incentivized local manufacturing, which makes them much cheaper than imports.

.jpg&c=0&w=700)

Chevrolet has over 85 percent market share in Uzbekistan.

Daewoo went bust in 2000, and GM acquired the bankrupt Korean automaker, including its Uzbek car plant. Daewoos were rebranded as Chevrolets thereon (though many still survive as Daewoos). One such rebranded Daewoo model that is hugely popular is the Chevrolet Damas minivan, whose lineage goes back to the Suzuki Carry – our very own Maruti Omni. Daewoo had a license agreement with Suzuki to make the Carry and badge engineered it as the Daewoo Damas, which became the Chevrolet Damas after GM acquired Daewoo.

.jpg&c=0&w=700)

Other cars stemming from the GM-Daewoo parentage and family to us are the Cruze, Spark, Beat, Optra and Matiz, but they have different names in Uzbekistan. While Chevrolet continues to dominate the Uzbek market, Chinese brands are slowly making inroads with their EVs.

Journey through time

This road trip to Uzbekistan brought back vivid memories of my drive on the Silk Road three decades ago. The 13,000 km expedition in a convoy of Mahindra Armadas spanned eight weeks and six countries. We began in Bukhara in Uzbekistan, traveled East into China, crossed the Taklamakan Desert, turned South into Tibet, continued to Nepal, and then made the final journey back to Delhi. It was a different world in 1994. The newly formed Uzbekistan had replaced the ruble with its own currency, the sum, which was so ridiculously weak that coins were worthless, making phone booths obsolete and unusable overnight.

.jpg&c=0&w=700)

Three decade ago, we had done a 13,000km expedition in a convoy of Armadas on the Silk Road.

Of course, there were no mobile phones back then, and even regular calls from Uzbekistan to India were nearly impossible. The Armadas, powered by the hardy but crude Peugeot 2.1 liter XDP 4.90 diesel engine, were horrible and pulling to drive. The only thing we had for entertainment was a cassette player and a small selection of tapes we replayed endlessly. There was no power steering, and operating the 4-speed gearbox required strong biceps. The 62hp engine was noisy and gutless, belonging to an age just before the common rail turbo-revolutionised diesels. But back then, the Armada was the plushest SUV you could buy in India, and the Soviet-built Ladas in Uzbekistan weren’t any better.

.jpg&c=0&w=700)

What hasn’t changed, of course, are the ancient monuments like the Registan Square in Samarkand, which was a great photo op for the Armada.

Also See:

.jpg&c=0&w=700)

.jpg&c=0&w=700)

.png&c=0&w=700)